The European Parliament opened Pandora’s box for Cyprus and its political system following the release of the now-famous Pandora’s Papers that exposed countries, politicians involved or connected to dirty money and the business of hiding it.

In a vote last Thursday, it adopted a resolution by 578 votes in favour, 28 against and 79 abstentions, as members of the European Parliament identified what they see as the most urgent measures the EU needs to take to close loopholes that currently allow for tax avoidance, money laundering and tax evasion on a massive scale.

They also called for legal action to be taken by the Commission against EU countries that do not properly execute existing laws.

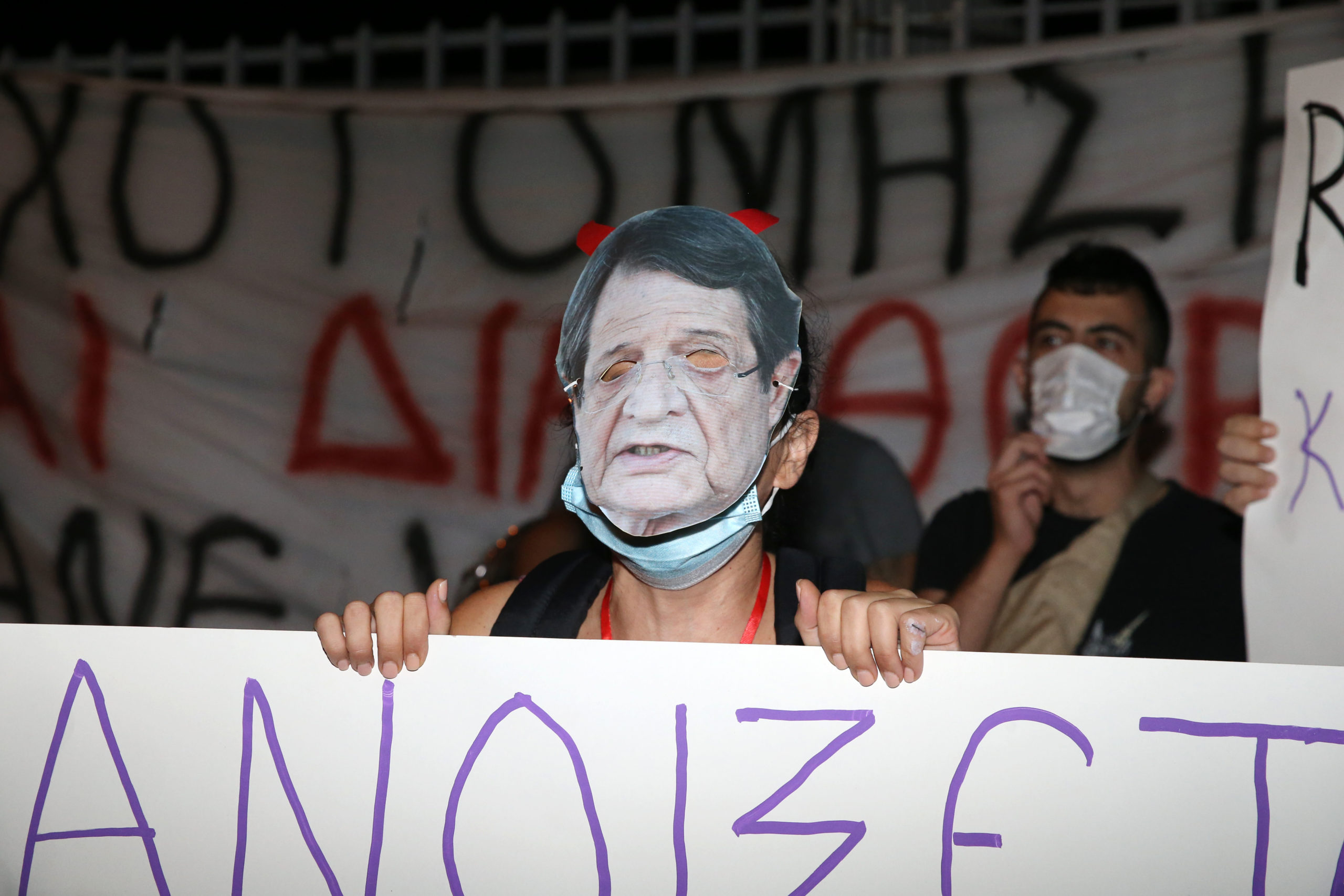

MEPs reserved particular criticism for present and former prime ministers and ministers of EU member states whose activities were revealed by the Pandora Papers, including Andrej Babiš, Czechia’s Prime Minister, Nicos Anastasiades, President of Cyprus, Wopke Hoekstra, Dutch Minister of Finance, Tony Blair, former British Prime Minister, and John Dalli, former Maltese Minister and EU Commissioner – all of whom were mentioned in the Papers.

Ilham Aliyev, the President of Azerbaijan, and Milo Đukanović, the President of Montenegro, were criticised directly in the resolution.

It called for the EU to blacklist tax havens and regulate golden passport and residency schemes, the last pointing to the Cyprus scandal exposed only a year ago by Al Jazeera, which led to the resignation of the Speaker of the House and an opposition MP.

It also led to a massive independent investigation that revealed colossal irregularities related to the citizenship by investment programme made by some of the world’s top criminals, such as Jo Low.

The investigation revealed many high-profile cases that date back more than a decade when the scheme was less popular but still badly operated under the previous leftist government.

As expected, the naming of President Anastasiades sparked both domestic and foreign criticism for the role of the law firm that bears his name in aiding and abetting Russian oligarchs in hiding money.

Anastasiades denied the allegations, and the government spokesman said earlier last week that the president welcomes the investigation.

But given the position of his party’s members of the EU parliament towards the resolution, it is clear that they are not very enthusiastic.

Three decades

Over the past three decades, Cyprus became famous among global elites for all the wrong reasons.

In the ’90s, following the war in former Yugoslavia, the Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic moved hundreds of millions in foreign currency to Cyprus, mostly received by state custom authorities.

The money arrived in Cyprus in ways that cocaine arrived in the ’80s and ’90s in the United States, in bags.

Officials of the Milosevic regime operating outside the UN embargo restrictions brought bags full of money to Cyprus with the full cooperation of the local police, customs authorities, the Central Bank of Cyprus, and the government’s support.

The money was then transferred to a nearby branch of the now-bankrupt Laiki Bank for counting, according to people with first-hand knowledge of the matter that gave interviews to local news media over the years.

Few, however, have actual knowledge of the whereabouts of these funds.

Years later, when the scandal broke out, the political system kept silent.

No political party felt it was necessary to call for an investigation.

No Attorney General was moved by the events or the information leaked over the years to launch a criminal investigation.

When events like these happened, there was bound to be a fallout.

For one, it made Cyprus famous as a tax haven and a money-laundering machine similar to the British Virgin Islands.

But according to the book “The Laundromat” by Pulitzer Prize winner Jake Bernstein, the “Tax havens are remarkably cohesive communities.

The financial services industry dominates. (In the case of Cyprus, this industry is mostly the big accounting and big law firms.)

“Local elites follow the cash, joining the industry or servicing it in other ways.

Business interests and the political establishment become intertwined.

Once the industry is established, the social controls in small, isolated communities activate on behalf of the industry.

“Locals accept a certain degree of corruption in the interest of keeping the money flowing. Those who resist are cowed into silence, ostracised, and – if they persist sometimes imprisoned or exiled.”

This short but dead accurate definition describes Cyprus.

In 2013, when Nicos Anastasiades became president, he was faced with a bankrupt state and bankrupt banks.

At the crucial Eurogroup in March 2013, EU leaders supported the idea of deposit haircut as the only sustainable measure to keep the economy and the banking system running.

Some people feel that it was a bad measure.

In reality, when things come to this, every measure appears to be bad.

The haircut on deposits in the two systemic and troubled banks was the least painful and most effective measure to restore confidence in the system. It worked.

Mostly the rich clients of those two bankrupt banks paid the heaviest price.

But the decision was also guided by the memories of the Milosevic scandal and the knowledge that Cyprus remained heavily dependent on the business of laundering money.

In his book ‘McMafia’, Misha Glenny wrote: “Israeli police have estimated that these Russians laundered between $5 and $10 bln through Israeli banks in the 15 years following the collapse of communism.

“This is a significant sum for a small country like Israel.

“But it is less than 5% of the huge capital flight from Russia during the 1990s, and it pales beside comparable countries such as Switzerland ($40 bln) or the perennial champion of the Mediterranean league, the Republic of Cyprus, which as early as the end of 1994 was processing $1 bln of Russian capital a month.”

It is clear that no matter what the ideological flavour of the ruling party in Cyprus, the current system of political financing not only allows but also encourages the pursuit of dirty money and the spoils of laundering it.

Some suggest this business stood in the way of solving even the Cyprus problem as opportunities for the reunification of the island sponsored by the UN were rejected by those who feared the loss of their lucrative business.

Career politicians stood ready to support them.

If Cyprus is to restore trust among its people and its allies, there must be a change.

It must move away from dirty foreign money that corrupts its institutions, politicians, and ultimately its future.

Its survival hangs in the balance.

Michael S. Olympios is an economist, business advisor, Editorial Consultant to the Financial Mirror