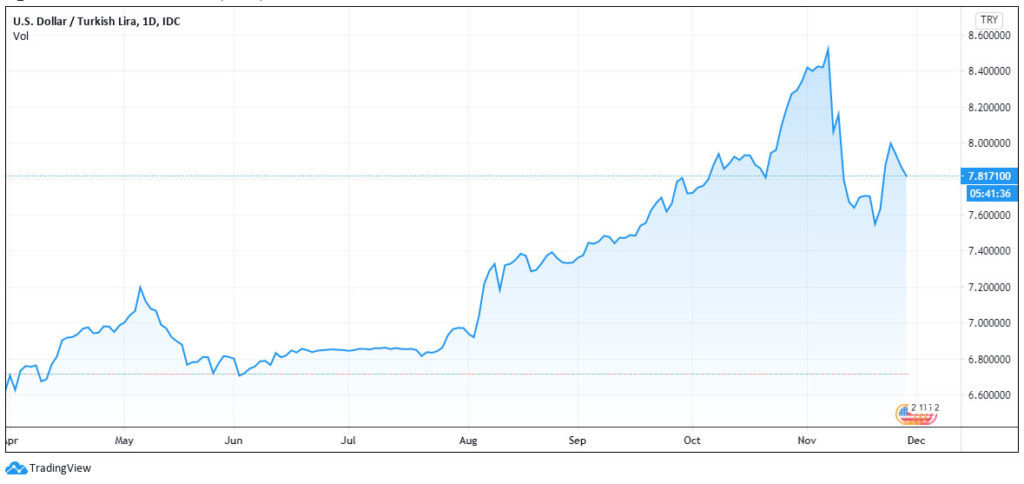

Enjoying a 12% rally since hitting a record low two weeks ago, the Turkish lira is now caught in a tug of war between foreign investors on the one hand, who cheered a big rate rise and government reform promises, and the locals who remain cautious and are stocking up on gold and dollar purchases.

The lira’s performance had been boosted by Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s pledge of a new market-friendly era for the economy, marked by the sacking of the central bank chief, and replacement of finance minister Berat Albayrak who is also the president’s son in law, earlier in November.

The currency enjoyed a newfound rebound, currently trading at 9.28 to the euro and 7.82 to the dollar, the stockmarket was soaring, and officials were talking about the need to reform the courts and keep inflation in check.

Within this context, justice minister Abdulhamit Gul, who has presided over a sweeping crackdown against government opponents since 2017, has discovered a passion for the rule of law.

Gul has been asking judges to comply with constitutional court rulings and help improve the climate for much needed foreign investors, especially at a time when the economy contracted by nearly 10% in the second quarter.

In the following weeks after the policy change and replacement of the head of the central bank and the economy minister, foreigners snapped up $5 bln in Turkish assets, based on bankers’ calculations.

This week, however, Turkey’s currency slid back 5% as Turks and local companies stepped in to buy $2.5 bln in hard currency at what was seen as a discount, and bankers say larger firms may be in the market for hard currency to meet rising foreign debt obligations.

According to a Reuters report, at $228 bln foreign exchange holdings in Turkey have never been higher and a major reason is imports of some $22 bln of gold this year – a favourite store of value for Turks, especially in uncertain times.

“The people are buying gold after selling their cars or houses, or just bringing their money to keep it as gold,” said Mehmet Ali Yildirimturk, a shop owner in Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar and deputy head of the city gold shops association in comments to Reuters.

“The pledge of economic reforms created an optimism in the market, but these promises need to be fulfilled with actual steps,” he said.

Blaming foreigners

Turkey’s Erdogan had long been blaming foreigners and high interest rates for two bad economic slumps and a more than 50% drop in the lira’s value since early 2018.

For more than two years, Erdogan had relied on son in law Albayrak to run the economy, with the former economy minister quoting his father in law in saying that exchange rates did not matter, as foreigners were dumping Turkish stocks.

In a response, banks dished out credit at rates below inflation to revive growth, the lira sank by over 40% against the dollar, burning a hole through the savings of millions of Turks. At least $100 bln in precious foreign reserves have gone up in smoke in an abortive attempt to salvage the currency.

When Erdogan finally put his foot down, son-in-law Albayrak stepped down, he sacked the central banker, replacing him with Naci Agbal, considered to be a rival of Albayrak.

When Erdogan finally put his foot down, son-in-law Albayrak stepped down, he sacked the central banker, replacing him with Naci Agbal, considered to be a rival of Albayrak.

The change in Erdogan’s tone has been remarkable.

The president, a sworn enemy of high interest rates, now says Turkey may have to swallow “a bitter pill”, meaning a dose of austerity. On November 19, the central bank duly imposed a spectacular rate rise of 475 basis points.

Yet, there is a limit to how far Erdogan is willing to go to save the lira.

He will have to deal with discontent within his own party ranks over the way he handled the economy, keep his allies at the ultra-nationalist nationalist movement party (MHP) happy, while having to gain the trust of the West with democratic reforms.

A group of 30 to 40 ruling-party parliamentarians are said to have threatened to defect to the opposition unless Albayrak resigned. The overhaul of Erdogan’s economic team has at least bought him some breathing space.

For all the recent talk of reforms, Erdogan is not about to loosen his grip on national institutions, give up on growth or stop tormenting opponents.

His prosecutors recently started an investigation into Ekrem Imamoglu, the opposition mayor of Istanbul, for criticising one of the president’s pet projects, a canal between the Black and Marmara Seas.

Even if Erdogan were sincere about democratic reforms and the need to patch things up with his western partners, the coalition he has sealed with his country’s ultranationalists, will make it difficult for him to take the right steps.

“He has locked himself into this path,” Ozgur Unluhisarcikli of the German Marshall Fund, another think-tank, was quoted by the Economist as saying.

“I can’t see how he can make substantial changes without destroying the alliance structure he has set up,” added Unluhisarcikli.