By Charles Ellinas

The International Energy Agency (IEA) published a special report earlier this month on ‘The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transition’, a subject that has not received the attention it deserves.

The key conclusion reached by the IEA was that in the transition to clean energy, critical minerals would bring new challenges to energy security.

Today’s mineral supply and investment plans fall short of what is needed to transform the energy sector, raising the risk of delayed or more expensive energy transitions.

The IEA emphasises that new and more diversified supply sources will be vital to pave the way to a clean energy future.

Without these, energy transition could be delayed by supply challenges and high mineral prices, opening up new opportunities, including for Cyprus.

Global mineral supply

The Paris Agreement and the increasing commitments to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 are “turbo-charging demand for minerals”, while investments in mining lag behind.

All new technology required to support renewable and clean energy applications requires more minerals than conventional energy sources.

As the IEA points out, “a typical electric vehicle (EV) requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car, and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant.”

As energy transition gathers pace, clean energy technologies are growing fast, putting increasing pressure on mineral resources and markets.

This could affect the future manufacture of EVs, hydrogen, batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines:

- Lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, and graphite for batteries.

- Rare earth elements for wind turbines and electric vehicles motors.

- Copper, silicon, and silver for solar PV.

- Copper and aluminium for electricity networks.

According to the IEA, “in a scenario that meets the Paris Agreement goals, their share of total demand rises significantly over the next two decades to over 40% for copper and rare earth elements, 60-70% for nickel, and cobalt, and almost 90% for lithium.

EVs and battery storage have already displaced consumer electronics to become the largest consumer of lithium and are set to take over from stainless steel as the largest end-user of nickel by 2040.”

The IEA estimates that mineral requirements to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 “would require six times more mineral inputs in 2040 than today.”

There is no shortage of mineral resources, but recent price rises for cobalt, copper, lithium, and nickel highlight how supply could struggle to keep pace with the world’s climate goals.

The rising importance of these minerals means that energy policies must consider availability, cost, investment requirements, vulnerabilities, and security of supplies, especially of the more critical minerals.

China, for example, controls nearly 90% of rare earth elements.

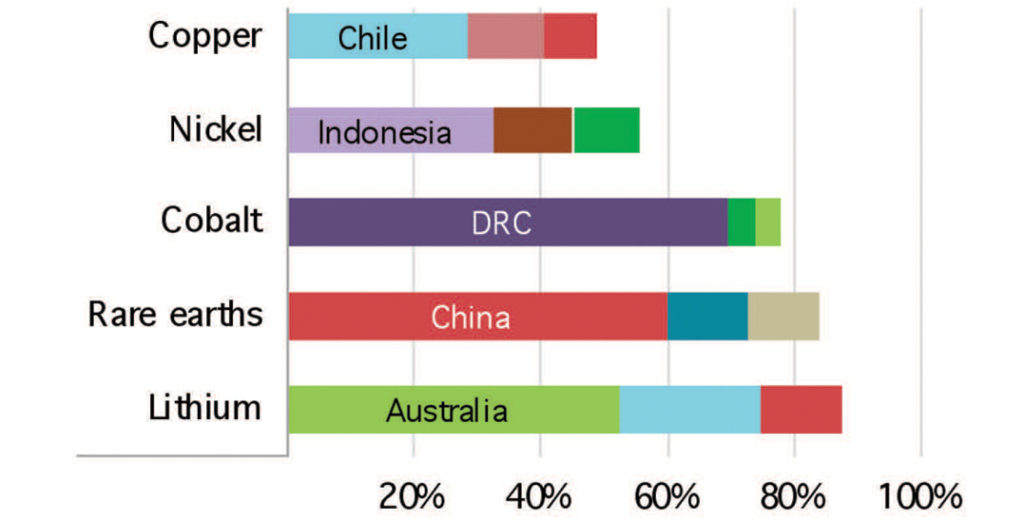

The IEA states that the production of critical minerals needed for clean energy technologies is much more concentrated than in the oil market.

For example, in some cases, cobalt, rare earth, and lithium, the three top producer countries, generate over 75% of supplies.

The IEA warns that today’s investment plans are geared to a world of gradual change.

Still, given long lead times for new projects, an accelerated energy transition could quickly see demand running ahead of supply.

It is then not strange that the security of mineral supply is gaining importance in the debate for energy security.

As Fatih Birol, IEA’s executive director, pointed out, “the data shows a looming mismatch between the world’s strengthened climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals that are essential to realising those ambitions.”

Without appropriate planning and action, energy transition risks being delayed by availability and increasing costs of critical minerals and supply disruptions.

Opportunities in Cyprus

These developments could also bring new mineral exploration opportunities to Cyprus, where, already, high-quality copper mining is proving to be quite promising.

Other mineral resources include sulphide, manganese, cobalt, gold, and chromite.

Mining companies operating in Cyprus include Amax Minerals, Ariana Resources, Caerus Mineral Resources, Chesterfield Resources, Hellenic Mining, Jubilee Metals Group, and Venus Minerals.

This year, Ariana Resources announced the commencement of diamond drilling on the Magellan Project through its association with Venus Minerals Ltd.

Meanwhile, Venus Minerals is exploring and developing copper and gold in Troodos, having made some promising discoveries.

Following exploration, the company confirmed that “Cyprus is home to significant untapped minerals deposits.”

Chesterfield Resources is also progressing its project in Cyprus, exploring primarily for copper, but has also identified strong gold potential.

The latest venture is by Caerus Mineral Resources, which obtained 14 of the island’s 27 historical copper mines earlier in the year.

In early May, Jubilee Metals Group joined Caerus to explore for copper and gold in waste stockpiles associated with these mines.

The extraction of copper in Cyprus dates back to the 3rd millennium BC.

There are references of copper exports from Alasia (Engomi – my birthplace) to Syria in the 18th century BC and Egypt in the 14th century BC.

The Roman word cuprum is derived from the name of the island.

The Romans called the new metal “aes cyprium” – Cypriot alloy.

Increased demand and prices are now bringing an opportunity for an ancient industry to return to its origins.

Dr Charles Ellinas is Senior Fellow at the Global Energy Center, Atlantic Council