DBRS Morningstar considers that most advanced economy sovereigns have adequate fiscal space to implement temporary measures to mitigate the adverse impact of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19).

The Coronavirus Quandary: This is Going to Hurt

The response to coronavirus places governments in a difficult dilemma. Efforts to slow the spread of the virus are needed to avoid overwhelming health care systems. However, the immediate economic impact of aggressive social distancing and widespread travel restrictions cannot be fully offset in the near term, even with sizeable fiscal stimulus programs. The timing and vigour of economic recoveries will hinge on two considerations: (1) governments gradually easing travel and other restrictions while health care experts and providers come to the rescue with effective prevention and treatment options; and (2) effective monetary and fiscal stimulus measures. Support measures will have a cost and government financial balances look set to deteriorate across global sovereigns.

Thus far, the measures outlined in our separate commentary appear sufficiently targeted and temporary to avoid any adverse rating implications. The positive effects of these measures on prospects for an economic recovery combined with negative real interest rates across most of the major economies suggest the costs will be manageable. Nonetheless, a few of these sovereign ratings – and particularly those toward the left-hand side of the exhibits shown below – will necessarily rely on policies that preserve economic resilience and a medium-term commitment to fiscal consolidation. The primary downside risk is that of an uncontainable outbreak with relatively ineffective treatment options, prolonged restrictions on travel and group gatherings, and a sustained rise in risk aversion and global savings. DBRS Morningstar considers this outcome unlikely, given past patterns associated with disease outbreaks. Nonetheless, a more prolonged shock would create increased risks of policy missteps or policy paralysis, which could yet pose risks to some sovereign ratings.

Public Sector Balance Sheets Are Not Fully Repaired, But Other Credit Fundamentals are Stronger

The 2008-09 global financial crisis and subsequent European debt crisis left many advanced economy sovereigns with higher debt burdens. Debt/GDP ratios are materially higher for most sovereigns, particularly for the so-called periphery countries in Europe, France, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States.

However, in the context of a persistently low interest rate environment, the cost of carrying these higher burdens has fallen for most of these same sovereigns. Aside from Australia, which still exhibits a relatively low level of debt as well as low interest costs, only a few of the Euro Area sovereigns (Spain and Portugal) have seen interest costs increase relative to 2006.

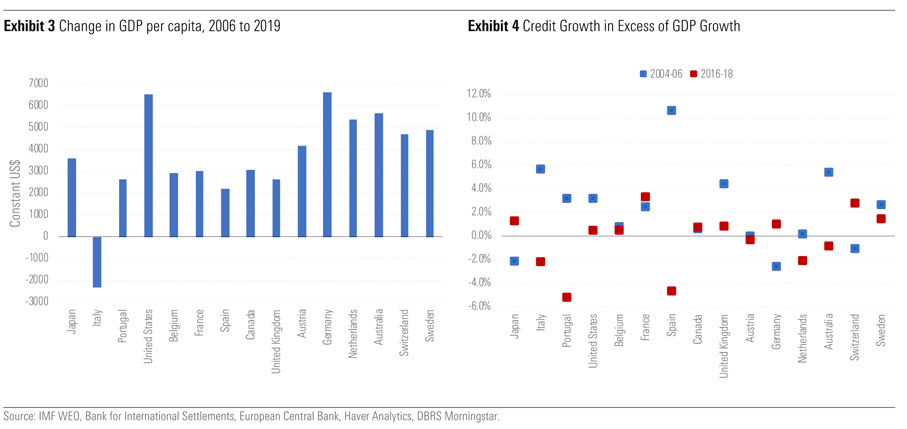

Economic fundamentals are also stronger across most of the major economies. Although growth in 2019 was relatively weak for most of the Euro area countries and in Japan, these same economies have fully recovered from the financial crisis, with the exception of Italy (BBB (high), Stable), where DBRS Morningstar has concerns about the weak growth environment (See COVID-19 tests Italian Resilience). Among this group, per capita GDP growth has generally been higher in the less indebted economies.

The United States nonetheless continues to stand out: a significant increase in indebtedness combined with a still large structural deficit has done little to reduce the dynamism of the U.S. economy. DBRS Morningstar views the U.S. as having qualities of innovation and flexibility that put it in good stead to weather the crisis. Unemployment levels have come down considerably since their peak amid the global financial crisis. With only a few exceptions (Spain, Italy), unemployment is down below its 2006 level. This is particularly true of Germany, as well as Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal and the United States. In addition, the financial excesses of the pre-global financial crisis years have not returned. Global banks have higher levels of capital and are better positioned to withstand a global downturn.

Commitments to Fiscal Consolidation Have Been Broadly Upheld and Are Likely to Remain Intact

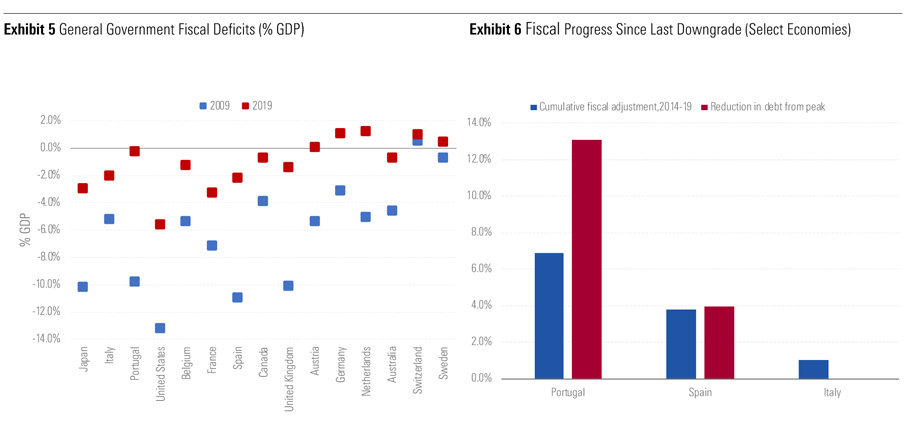

The major global recession in 2009 combined with large-scale support to financial systems generated significant government deficits. As economies recovered, most of these same governments delivered on early commitments to fiscal consolidation.

The United States delivered a larger adjustment than the one shown below, with the deficit reaching 3.6% in 2015, only to be partially reversed prior to this outbreak amid shifting government priorities toward increased spending and income tax cuts. A number of countries that started off in a relatively strong position (e.g., France, Italy), have taken sufficient actions to broadly stabilize debt but have fallen short of structural balance targets.

It must also be noted that a few advanced economy sovereigns did not make it through the last decade without rating downgrades: Italy, Spain, and Portugal were all downgraded by DBRS Morningstar during the Euro area debt crisis. Since their latest downgrades in 2012, Spain and Portugal have achieved considerable progress in reducing deficits and debt, an achievement reflected in subsequent upgrades.

Although Italy’s starting point was stronger (with a deficit of less than 3% of GDP in 2012), weak growth prospects have pushed debt levels gradually higher, and Italy’s ratings remain at a postcrisis low.