Analysis: Morningstar DBRS

Just a day to the UK general election on 4th July and a change in government looks imminent.

The Labour party has continued to lead in the voting intention polls and if polls prove right, Labour will form the next government. After 14 years of a Conservative-led government, a change to Labour will mark a notable difference in UK politics. Despite the change in power, we expect the next government to follow broadly prudent economic policies.

Nevertheless, the challenges that the next government will face are significant, including growing the economy, improving public finances and services, and strengthening energy security. In this commentary we take a look at these three key challenges for the new government and the policy pledges that the Labour party presented in its manifesto during the election campaign, which could potentially have credit rating implications for the UK (rated AA, Stable Trend).

An Early General Election Amid Gradually Improving Economic Conditions

The next general election was expected later this year, but in a surprise move and despite the Conservative party being behind in the polls, in May Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called elections.

Economic conditions have been gradually improving so far this year, but the polls did not improve for the Conservatives. Since elections were called almost six weeks ago, the Labour party’s lead in the voting intention polls have remained at around 20 points. The Labour party has consistently led in the polls since December 2021.

The Challenges Are Significant and the Policy Proposals Are Ambitious

Notwithstanding the strong mandate that a Labour government seems likely to gain, the challenges it will face over the next parliament are significant. We highlight three key challenges related to the credit analysis of the UK:

-

Growing the Economy, Including Increasing Productivity and Strengthening Trade Links

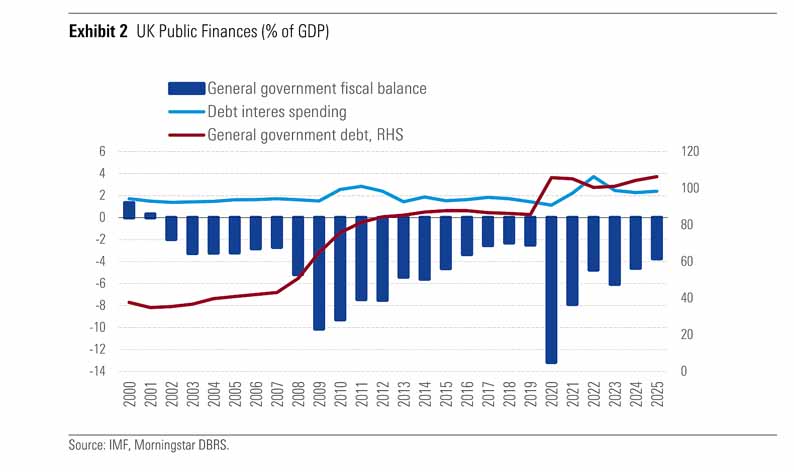

For years the UK economy has been struggling with persistent low growth, mostly reflecting lower productivity growth. Brexit, the pandemic and the energy price shock have weighed on business investment in recent years (see Exhibit 1), while a rise in long-term sickness combined with Brexit effects seems to have also slowed growth in the labour force, with an increase in labour inactivity.

The Conservative government adopted measures to increase labour market participation and business investment, but the impact of their policies has been limited so far.

At the same time, since 2020 the UK’s export performance has weakened, with trade volumes falling. Thus, post-Brexit, trade policy has gained a more prominent role as the UK tries to secure stronger trade links around the globe. Since leaving the EU, the UK has signed just over 70 free trade agreements, of which 68 are rollover deals and three are new deals, with Australia, New Zealand and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), though the latter is not yet enforced. When elections were called, the UK was negotiating a few trade deals, including with the Gulf Countries Council (GCC) and India, while trade negotiations with Canada were suspended at the beginning of 2024 and negotiations with the US have not progressed since October 2020. Over the longer term, uncertainty remains over the lasting impact of the UK-EU Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) and that of new trade deals on trade, investment and migration, and ultimately on potential output of the UK economy.

Looking ahead to the potential economic policy proposals, the Labour party manifesto revolves around the party’s already known five missions: reviving economic growth, making Britain an clean energy “superpower”, reducing crime, reforming childcare and education systems, and building an “NHS fit for the future”. In our view, the Labour’s economic plan seems ambitious and is subject to execution risks, and even if fully implemented, the results will take time to materialise.

Looking ahead to the potential economic policy proposals, the Labour party manifesto revolves around the party’s already known five missions: reviving economic growth, making Britain an clean energy “superpower”, reducing crime, reforming childcare and education systems, and building an “NHS fit for the future”. In our view, the Labour’s economic plan seems ambitious and is subject to execution risks, and even if fully implemented, the results will take time to materialise.

Boosting economic growth seems to be at the core of the Labour manifesto. Under Labour, the government looks likely to have a bigger role on the economy. In particular, Labour is set to launch a new industrial strategy, which involves an advisory Industrial Strategy Council, to support specific economic sectors, including financial services, automotive, life sciences and creative sectors. Trade policy is set to be aligned with the industrial strategy.

Furthermore, to increase investment Labour has proposed the creation of a National Wealth Fund, with capital of GBP 7.3 billion (0.3 % of GDP) and a mandate to support growth and clean energy and to attract private investment. Labour has also pledged to adopt reforms to the pension fund sector with the aim of increasing investment from these funds in the UK economy. Moreover, full expensing for capital investment will be retained. Importantly, a Labour government intends to develop a ten-year infrastructure strategy aligned with the industrial strategy to drive infrastructure investment. A reform to the planning system to build infrastructure and housing is also on the table.

Construction could certainly provide a boost to the economy. To increase labour market participation, Labour has pledged to tackle long-term sickness and to reform employment support.

-

Improving Public Finances

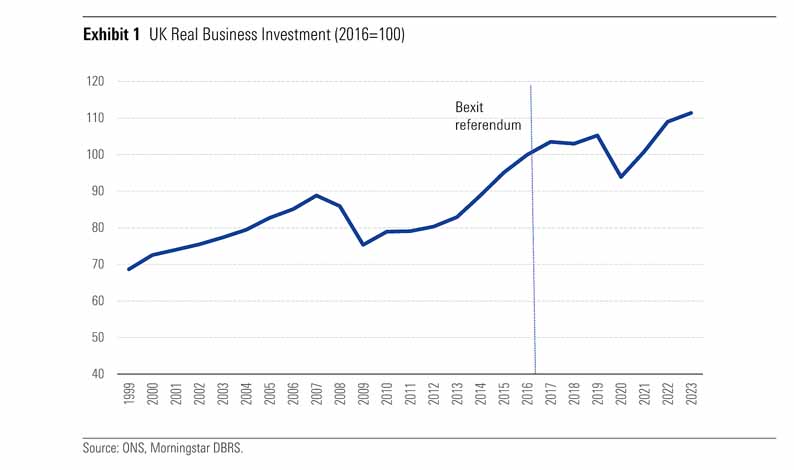

Over the past 16 years, the UK fiscal position has been hit by successive crises and shocks, including the pandemic and more recently the energy shock, which required substantial fiscal support and led to large deficits and a high government debt ratio. From a moderate level of 43.2% of GDP just before the global financial crisis in 2007, the general government debt ratio more than doubled to 101.1% in 2023 (see Exhibit 2). Thus, reducing the high government debt ratio and creating fiscal room will remain a priority for the government. This is especially the case as the cost of debt is more expensive after the low interest rate environment ended. The latest projections from the OBR in March this year, presented together with the Spring Budget, show the general government debt ratio peaking at 104% of GDP in 2026 before starting to fall.

The projections incorporate the Conservative government’s measures, including lower taxes in the near term, and the reform of the non-domicile tax regime and increase in some taxes in later years.

In its manifesto, the Labour party has pledged to follow the UK fiscal rules indicating commitment to fiscal prudence. This means reducing the public debt ratio and the fiscal deficit below 3% of GDP by the fifth year of the rolling forecast. Labour’s fiscal plan includes increased spending in public services, particularly in the National Health Service (NHS), to be more than offset by increased revenues largely from the elimination of the non-domicile tax regime, reduced tax avoidance, and VAT on private schools. Moreover, Labour intends to partly fund its ‘Green Prosperity Plan’ with a temporary oil and gas windfall tax, with borrowing covering the rest. The corporation tax will be capped at 25%.

In our view, risks to the fiscal outlook will remain high, given the degree of uncertainty over some revenue measures. A bigger role of the state in the economy could also increase contingent liabilities. Moreover, partly relying on expected stronger economic growth to reduce the fiscal deficit and public debt leaves the fiscal position exposed to the risk of lower-than-expected growth.

A Labour government seems unlikely to present a budget with the first few weeks of government, as the presentation of a budget together with a full set of economic and fiscal forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) would require about ten weeks. Therefore, a new budget or fiscal event with updated forecasts seems more likely to be presented from mid-September.

-

Strengthening Energy Security and Meeting Climate Targets

With the UK being a net importer of natural gas, the energy shock in 2022 hit the UK economy hard, leading to high inflation and contributing to a deterioration in the UK current account deficit as a result of a terms of trade shock. Therefore, reducing the UK’s energy dependence on imported oil and gas has become a key policy goal. The Conservative government updated its energy security strategy in 2023. On climate ambition, the UK has decarbonised its economy notably over several years, with its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions falling by about 53% from 1990 to 2023, more than many advanced economies, and now accounting for around 1% of total global emissions. The decline largely reflects the increase in renewables. Transport remains the main source of GHG emissions in the UK, followed by the energy sector. The UK’s commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050 is legally binding.

While Labour is also aiming to strengthen energy security and the UK’s legally-binding Net Zero Target (NZT) is unlikely to change, climate policies are likely to be somewhat different under a Labour government. One key proposal from Labour is the creation of a publicly-owned company “Great British Energy” to supply clean energy by investing in partnership with industry in clean technologies. A Labour government would provide initial capital of GBP 8.3 billion (0.3 % of GDP) to Great British Energy, which is set to be headquartered in Scotland.

In line with its mission of making Britain an clean energy “superpower”, the Labour party confirmed in its manifesto its commitment to clean energy by 2030. Through its ‘Green Prosperity Plan’, a Labour government intends to double onshore wind, triple solar power, and quadruple offshore wind by 2030, working together with the private sector. It has promised to invest GBP 6.6 billion to improve energy efficiency in residential properties. It has also pledged to invest in carbon capture and storage, hydrogen and marine energy; to give nuclear power a key role in achieving energy security and clean power; and to maintain long-term energy storage. Equally, it has promised not to revoke existing licences in the energy sector and that oil and gas production in the North Sea will be managed in the coming decades to avoid putting jobs at risk. However, Labour committed to not issuing new licences to explore new oil and gas fields – in contrast to the Conservative party. It would not grant new coal licences either and would ban fracking.

Regulatory certainty would help investors. A new Energy Independence Act would set the framework for energy and climate policies, with a reform of the energy system with stronger regulation and upgrade of the national grid also on the cards. Labour is in favour of introducing a carbon border adjustment mechanism, to protect British industries during the decarbonisation of the economy. It has also promised to reinstate the 2030 target for phasing-out sales of new cars with internal combustion engines, which was relaxed to 2035 under the Conservative government.

It would also reverse the decision to prevent the BoE giving consideration to climate change in its mandates, and would mandate UK-regulated financial institutions and FTSE 100 companies to implement transition plans aligned with the Paris Agreement. Likely reflecting the expectation of a higher degree of stringency in climate policies under a Labour government, the carbon price in the UK increased since the general election was called. Nevertheless, reducing the UK’s reliance on gas and achieving the NZT will be challenging, as it will require significant investment and the deployment of clean energy installations take several years.

Labour’s Plans Have Potential but Also Considerable Risks

Overall, the broad expectation is that the Labour party will win a majority in the UK general election. Despite a change in government from Conservative to Labour, we expect a Labour government to follow prudent economic policies, with the potential of boosting growth. In its manifesto, Labour has pledged ambitious plans to grow the economy and step up clean energy, while returning public finances to a sound position. Although further details on concrete policies are yet to be presented, we see execution risks in Labour’s plans, largely because of the scale of the investment needed.

Moreover, poor effectiveness of the plans could lead to lower-than-expected growth, with adverse implications for the fiscal outlook. Other risks could come from a failure to attract private investment and the external environment, including geopolitical risks and weak external demand.