Freedom of expression is one of the fundamental principles of democracy.

And if we want to believe that we live in a true democracy, then this freedom, be it in art or the media, ought to be respected, not persecuted.

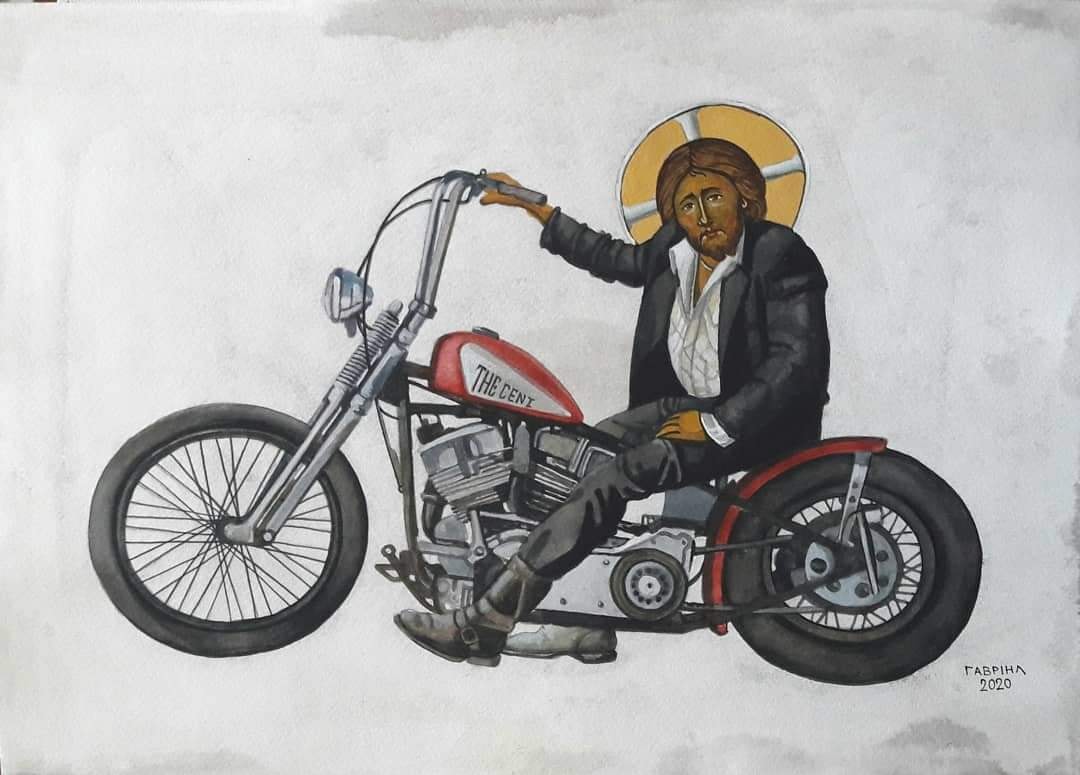

The fuss created this week over the work of an art teacher, which he labelled as ‘anti-establishment art’, takes us back to the Dark Ages, the Inquisition, the burning of books and more recently the controversial installations by Damien Hirst of animals preserved in formaldehyde.

This level of intolerance shows that Cyprus society is still not mature enough to accept change or anything different, regardless of what politicians and others advertise.

It is this conceitedness that drove the artist in question to express his disgust at the establishment, not by throwing rocks on police cars or shooting people, but with an ingenious stroke of the brush on an innocent canvas.

What, then, is ‘proper’ art? Must it be inoffensive? Who determines what is ‘disturbing’?

The argument that erupted is also well-timed to divert public attention away from scandals and corruption, with politicians and church leaders up to their necks in dirty dealings, especially over issuing passports for cash or allowing the development of urban monstrosities that destroy the environment.

In the absence of home values instilled by parents, teachers are supposed to step in and guide our children to help them become better people.

Furthermore, a few good art teachers should be commended not just for enlightening students about colours, symmetry, and shades, but also for helping them think unconventionally, out-of-the-box. Teenagers don’t have to be the next Dali or Picasso, but their minds should be allowed to roam freely and have healthy thoughts, something that our leaders lack.

Covering up parts of the human anatomy or blowing up sculptures is the finest work of ISIS and other backward societies, not ours.

In the 16th century, the Catholic Church was furious that one of the most magnificent frescoes by Michelangelo, covering the entire altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, depicted nudes in the Second Coming of Christ and the final judgment by God of all of humanity.

After the Renaissance master’s death, the genitalia was censored by painting over them with draped fabrics.

Then came the late 19th-century Origin of the World by Gustave Courbet, a portrayal of a woman’s genitals and naked body that continues to stir controversy even today with Facebook censoring pages that use a picture of the painting.

And let us not forget Facebook coming to its senses after banning the Pulitzer prize-winning photo by Nick Ut of a nine-year-old Vietnamese girl fleeing American napalm bombings, probably one of the most powerful anti-war images ever.

More recently, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art refused to remove a 1938 painting, ‘Therese Dreaming’ by Balthus with a young girl sitting in a position that reveals her underwear after a petition criticised the painting for being sexually suggestive.

So, should we also place a leaf in front of Michelangelo’s David?

Controversial art is valuable as a medium for conversation.

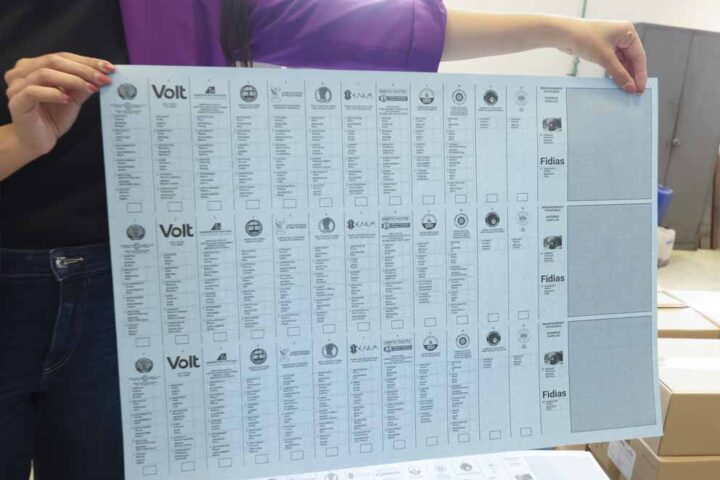

And what our society lacks, evident from the sorry turnout at local elections, is a healthy conversation.

If our youth do not converse, they are doomed to become machines that view the world in black and white or darker shades of grey.