By Moody’s Analytics

The U.S. labour market remains tight, but conditions loosened materially in June.

The modest decline in the number of job openings from May to June comes after May’s figure was revised downward by more than 200,000.

Openings are now at their lowest since April 2021, when COVID-19 vaccines were becoming widely available. Then, a coordinated rush from U.S. consumers back to spending on services and in-person activities caused a spike in firms’ demand for workers that has not yet been rebalanced.

The quits rate, a more reliable proxy for upward wage pressure, fell to 2.4% in June. For context, the quits rate averaged 2.3% in the two years before the pandemic.

The labour market was tight then, but inflation was hardly the concern it is today. June’s reduced quits rate offsets the surprising increase in May and is the kind of labour market development the inflation-fighting monetary policymakers of the Federal Open Market Committee are looking for.

Nevertheless, there remain 1.6 job openings for every unemployed person in the U.S. That is down from the 2:1 ratio reached a year ago, but still too high for central bankers to feel confident that wages are not threatening to perpetuate above-target inflation.

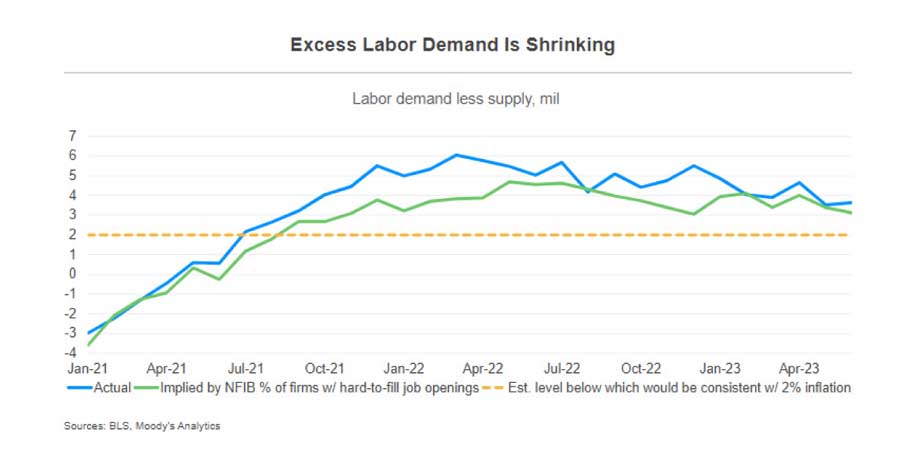

Labour demand, defined as the sum of employment and job openings, continues to exceed labour supply, or the labour force. However, this imbalance is shrinking. The gap between available jobs and workers was 3.6 million in June, down from little more than 6 million at its peak in March 2022.

The share of firms with hard-to-fill job openings, according to the NFIB Small Business Survey, has historically correlated well with job openings as captured by the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey and points to a moderately smaller gap between labour demand and supply of 3.1 million.

That said, Moody’s Analytics estimates that the difference between available jobs and workers needs to fall sustainably below 2 million to be consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

Therefore, it would still be premature for the central bank to declare victory on inflation, despite the encouraging signs of loosening labour market conditions.

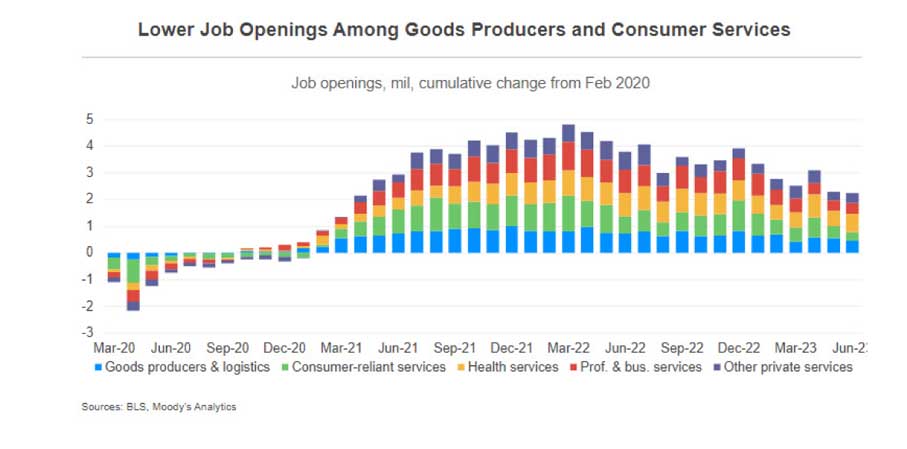

Goods, logistics, consumer services

The decline in job openings in June was largely concentrated among goods producers, logistics firms, and consumer dependent services. On the other hand, job vacancies in health services rose 24% in June and have largely moved sideways this year. Also, job openings in professional and business services barely budged in the second quarter.

Already, health services and professional and business services are the two most important industries with the largest imbalances between labour demand and supply.

The gap between available jobs and workers is equivalent to 4.7% and 5.9% of the labour force in professional and business services and healthcare, respectively. Since at least 2001, healthcare has historically faced more excess labour demand than other industries due to growing demand for medical care from an aging population.

The gap between available jobs and workers is equivalent to 4.7% and 5.9% of the labour force in professional and business services and healthcare, respectively. Since at least 2001, healthcare has historically faced more excess labour demand than other industries due to growing demand for medical care from an aging population.

However, prior to the pandemic, the difference between labour demand and supply in the healthcare industry never exceeded more than 3.8% of the labour force. Whether permanent or not, the pandemic seems to have worsened the demand-supply imbalance in the labour market for healthcare workers due to the stress and burnout it created.

On the other hand, we have observed a significant reduction in excess labour demand in consumer-dependent services since the end of last year, while labour-market imbalances are the least binding among goods-producing and logistics industries.

More productive in second quarter

The preliminary estimate of U.S. labour productivity from the Bureau of Labor Statistics exceeded our stronger-than-consensus forecast of 2.5% growth, coming in at an annualised 3.7% in the second quarter. Though measures of productivity are volatile and subject to revisions, the acceleration in the second quarter is encouraging.

On the inflation front, strong productivity growth means fewer wage increases are passed through to consumer prices.

Despite resilience in the labour market, conditions are starting to loosen. Wages continue to grow at a heady pace but appear to have turned over. The latest employment cost index shows wages and salaries were up 4.6% in the second quarter, relative to a year earlier. Though the Federal Reserve would like to see growth slow to 3.5%, the downward trend from 5% is encouraging.

The 3.5% estimate, given the central bank’s 2% inflation target, implies 1.5% trend growth in productivity. Our latest baseline forecast puts productivity growth a little bit stronger than that. In the near term, one reason to expect an acceleration in productivity growth is the subsiding degree of labour churn.

The declining rate at which people are quitting their job will boost productivity growth. When people quit a job to start a new one, not only do they pull in higher pay—a concern for the Fed—they also require training. This makes firms less productive in the near term. As the churn in the labour market starts to ease, this drag on productivity will ebb.

The declining rate at which people are quitting their job will boost productivity growth. When people quit a job to start a new one, not only do they pull in higher pay—a concern for the Fed—they also require training. This makes firms less productive in the near term. As the churn in the labour market starts to ease, this drag on productivity will ebb.

Another reason is demographic. Older workers have a career’s worth of knowledge and experience to lean on. As more baby boomers reach retirement age, this loss of expertise and skills will be a near-term headwind for productivity growth.

However, the seasoned experience of older workers also meant they were unlikely to be adopting new skills and embracing newer, more efficient technologies.

In other words, output per hour may be high, but it wasn’t likely to be growing very quickly. The share of the labour force age 55 and older peaked prior to the pandemic and will steadily decline for the next decade. This factors into our projections that labour productivity, near-term vagaries aside, is on an upward trend in the longer term.