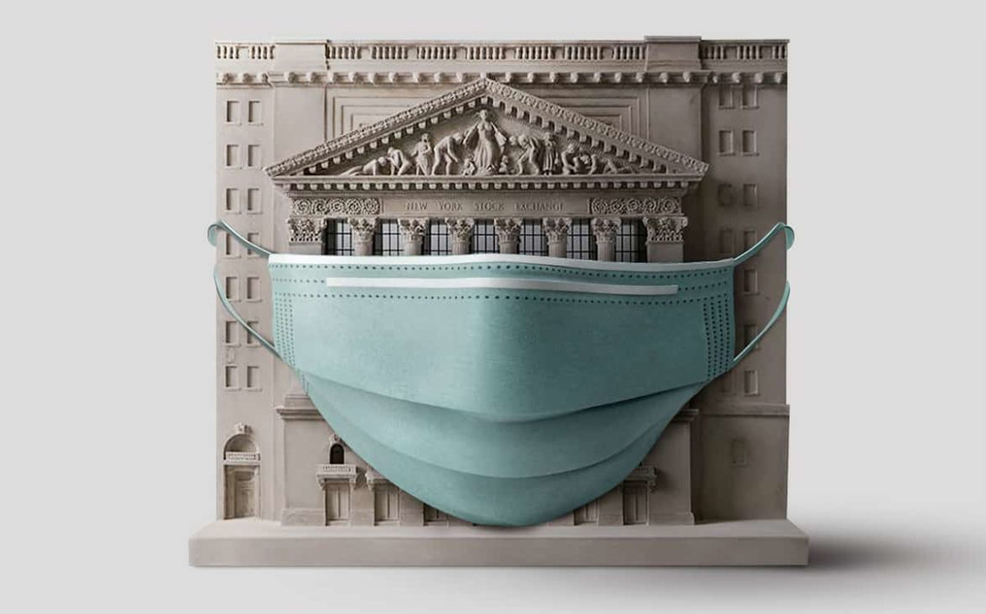

Credit Suisse recent woes, followed by the collapse of Greensill Capital and Archegos Capital last month, reminded everyone of the value of risk management.

But it did more than that.

It brought to the surface the weaknesses of a system hailed by many as impervious to bad practices and market thunderstorms a few years ago.

Financial and banking watchdogs have repeatedly stressed the importance of strong risk management and corporate governance.

Since the collapse of Enron and WorldCom in 2001, and later in 2008, the downfall of Lehman Brothers and RBS, governments and regulators have revisited the subject of risk management and corporate governance to fix weaknesses.

They proposed more independence and Chinese walls.

Compliance became so vast that it will soon become an academic degree like finance.

However, one of the least thought-through measures they took was to require more capital both for banks and financial services firms.

The rationale behind this measure was that bad things happen that inevitably result in losses.

So, the more capital you hold, the more losses you can absorb without scattering them around to clients and taxpayers in the event of an accident.

Banks won’t have to resort to deposits to cover their losses, while financial services firms won’t touch their clients’ funds.

Both measures are indeed absolutely essential to maintain the necessary confidence in the system, or people will simply avoid it no matter what the opportunity cost.

It all sounds good and reasonable. Or does it?

These measures hardly address the real issues that cause financial accidents in the first place.

It’s like requiring car manufacturers to implement new brake systems on their vehicles.

One would expect that both physical damages and fatalities will be reduced by reducing the impact, assuming the same level of driving dexterity.

When I was a college student in the United States, I read a book, “The armchair economist” by Steven Landsburg.

It pointed out that insurance companies provided discounts back in the ‘70s to owners of cars with seatbelts installed.

The book referred to a study “why seatbelts kill”.

According to the study, drivers felt more secure wearing seatbelts but were more careless with their driving.

Statistically, insurance companies had to pay more damages to accidents caused by vehicles with seatbelts than to those without.

So, the discount offered to owners of safer cars wasn’t justified.

Safer banks and financial institutions are not made because they hold more capital but know how to manage business opportunities and their risk prudently.

Bad apples

Despite efforts by the Central Bank of Cyprus and CySEC to address bad practices, markets will always have bad apples.

But they need to do much more if they want to prevent the sort of accident brought by Credit Suisse.

Regulators must be more vigilant when it comes to assessing the top brass of the regulated entities.

Similarly, they should conduct random checks on how the board runs its business and maintains risk management’s independence, a prerequisite for effective risk management.

According to the Financial Times, “two months earlier, Greensill Capital had been put on a watchlist by the Swiss bank’s risk managers in Asia…that might have raised more alarm at Credit Suisse…however warnings were repeatedly dismissed by the bank’s leadership in Zurich, London and Singapore.”

Why didn’t regulators catch that one?

Because they sit comfortably thinking that regulated entities have enough capital to absorb losses until one day someone will take such a complex bet that nobody will figure out the risk until it finally materialises.

What’s the solution?

Regulators should limit bonuses traders and senior managers can take home to make big bets unattractive.

On the other hand, it should be made mandatory that a certain percentage of bonuses should be linked to key performance indicators or KPIs that include sound risk management policies and internal compliance.

We have yet to hear of CEOs getting rewarded for driving safely.

Yet we keep hearing only of those who drive fast.

That’s why seatbelts kill. And that’s why capital buffers keep creating accidents in the order of billions as those of Credit Suisse.

ESMA, the European Banking Authority and the Single Supervisory Mechanism should rethink what really needs to be regulated based on how things are done and not how they like them to be done.

Michael S. Olympios is an economist, business advisor, Editorial Consultant to the Financial Mirror